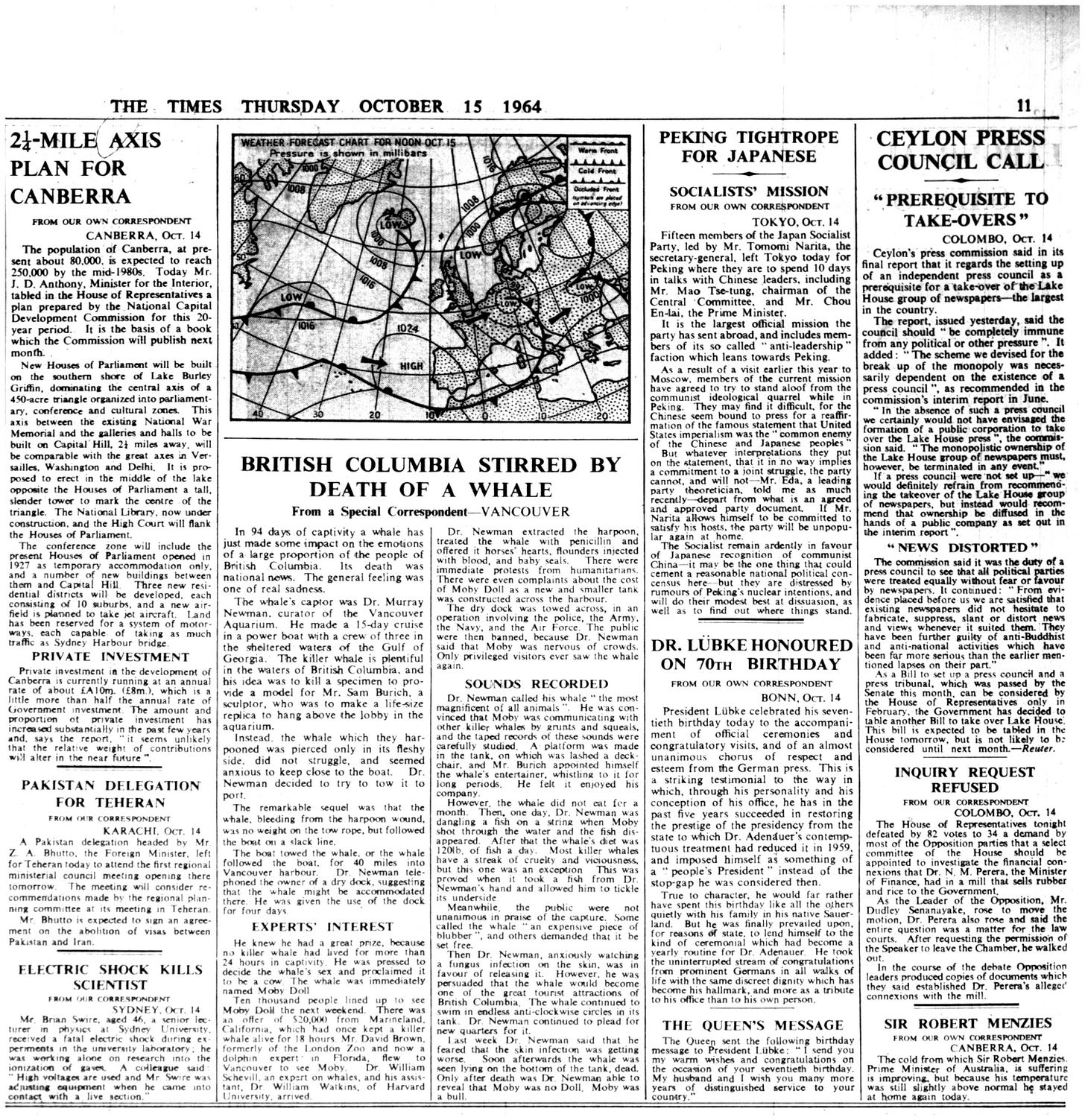

Sixty years ago today… October 9, 1964… the first orca ever displayed in captivity died in captivity in a makeshift pen at Jericho Beach in Vancouver. Here’s the story of Moby’s final hours from my book, The Killer Whale Who Changed the World. I’ve tried to add a bit of information to identify the players.

AT THE END of August, Moby Doll was looking pale. She was losing her sheen—her slick black skin was turning gray. Pat McGeer (the neuroscientist in charge of the orca’s care) was concerned. The whale may have looked healthy to the acoustics researchers two weeks earlier, but this couldn’t be a good sign. The experts from other marine parks told him to relax, that mammals changed color in fresher water.

Moby also had what appeared to be a fungal infection. Again, McGeer and Murray Newman (head of the Vancouver Aquarium) were worried that this had been caused by the water at Jericho. A skin specialist reassured them that the rash was nothing to worry about, and neither was Moby’s paler skin tone. McGeer deferred to the experts and told reporters: “I hope all the people of British Columbia soon have a chance to see the killer whale.” But McGeer and Newman still wanted the whale in saltier water ASAP—except they weren’t just dealing with bureaucracy but with enough red tape to drown a humpback.

Even if Moby wasn’t eating and her skin looked washed out, she hadn’t looked healthier or happier since the day she had been captured. She had broken out of her repetitive swimming pattern and appeared to be playing. She started slapping her tail and splashing her visitors; then she started leaping. Moby must have been working up an appetite, because on September 8, guards were certain they saw her eat a fish from the line. The next day, Moby finally, definitively, ended her hunger strike.

Newman was meeting Ted Griffin from the Seattle Marine Aquarium and Allan Williams, chairman of the West Vancouver parks commission—and the prime candidate to host the whale’s new pen. While Newman was chatting with Griffin, Williams tried holding the line for Moby, and for the first time, everyone could see her take the fish. Newman believed Williams was the first person to ever feed a killer whale. The small crowd at the pool cheered. Then Griffin fed the whale a cod. “It was electric,” recalled Griffin half a century later in an interview with PBS. For Griffin, it was a sign that his childhood dream of having his own killer whale—perhaps even riding his own whale—hadn’t been just a fantasy; he really did belong with these creatures. “From that point on, I knew I would risk everything, sacrifice everything, go to the end of the world to get a whale.”

Newman and his delighted visitors watched as Moby quickly devoured another hundred pounds of cod and a salmon.

The Sun headline the next day was “Whale Eats.” Newman was described as “elated.” He was also relieved. For the first time since bringing Moby Doll to Vancouver, he could finally allow himself to believe she was going to be all right.

The next day, the aquarium staff tried feeding Moby from the float with a shorter line, and McGeer went back to stuffing salmon with extra vitamins to combat the fungal infection. CBC TV breathlessly reported: “Moby Doll has started eating in a big way. For the first time since her capture in July, the killer whale has started to take large quantities of food. Yesterday she ate about a hundred pounds of dead fish . . . Today she had a similar meal . . . The whale seems to be enjoying her meals. Each time a fish is offered she nuzzles it with her big snout before taking it from the line.” Now that she was eating, Mobymania was back in full swing.

While Henry Bell-Irving served a brief stint as Vancouver’s acting mayor, he urged council to declare Moby Doll the city’s new official symbol. He felt it would be appropriate, not just because of the whale’s fame but because of her connection to the city’s origins before the white settlers arrived—a radical concept in 1964. “It would also be distinctive because it is part of our native Indian mythology,” he said.

Bell-Irving argued that any city could have a flower or bird represent it, but a coastal city should have an emblem that signified the coast—and killer whales were regularly seen in Vancouver’s harbor. Aquarium boosterism aside, the whale certainly seemed like a more inspired choice than the outline of city hall, which was the image that currently graced the copper plates that were presented to distinguished guests. The proposal was prompted by the impending arrival of American president Lyndon Johnson. Bell-Irving hoped the president could meet the whale, and if that wasn’t possible, that he could at least receive a miniature silver whale sculpture in honor of his visit.

Meanwhile, Moby’s appetite remained front-page news. The Sun featured a photo of Moby eating and reported that she had consumed a forty-pound lingcod, a five-pound salmon, four five-pound red snappers, and (though this seems unlikely) a horse’s heart and liver.

A few days later, Moby began approaching her keepers and waiting for them to drop fish into her mouth. She wasn’t prepared to take food off a long string, but she’d eat if the men hand-fed her. When it was clear that Moby wouldn’t try to eat her feeders along with her food, they stopped using lines and began hand-feeding the dreaded killer whale. The newspapers soon featured photos of Moby eating out of McLeod’s hand, then Newman’s.

Then Sam Burich (sculptor and harpooner) finally fed the whale. “Sam went from holding the food from the end of a pole to holding the food in his hand and having Moby come up and take it right out of his hand,” said Newman.

“When we realized we could feed it by hand and it wouldn’t take our whole arm into its mouth, it was amazing.”

Says McGeer, “When it started, everybody took a turn.”

Newman began publicly musing about having Moby jump out of the water to take the fish, like the dolphins in Marineland. Moby was less enamored of that idea. When Penfold tried to get her to leap for her supper, she swam to the center of the pen in protest. Then Penfold offered a couple of orange rockfish. When Moby saw the fish, she swam to the center of the pool, swatted the water, and didn’t come back to the float until Penfold offered another gray cod. After Penfold sliced the spines of the rock fish, Moby ate them. “By gosh,” said Penfold. “She’s training me.” Moby also played with Penfold when he ventured underwater in his scuba gear—in the safety of a wire cage—to get a closer look at her skin infection. When he turned his back, Moby would nudge the cage, then dart away and squeal.

Joe Bauer (Burich’s assistant) was one of the only regulars who didn’t spend time trying to feed Moby. “I did pet it [the whale] one time, but I was always too busy taking pictures. One time I touched it when I was visiting Sam. Sam very definitely fell in love with it.” Burich told reporters that the whale he’d called Hound Dog reminded him of “a great big cocker spaniel.”

McLeod didn’t feel like Moby was training him, but he knew she was bonding with him. After he started hand-feeding Moby, McLeod began rubbing her stomach—first with a broom, then with his hand. Soon he was scratching her fins and had Moby presenting a flipper and rolling over.

This was everything Newman had dreamed of and more. A killer whale liked getting belly rubs? The public would love that.

Everything was going so well that on September 29, the lead whale watchers finally took a break so that they could watch more whales—in the wild. Newman and McGeer went on a collecting expedition and brought Colonel Matthews to discuss how they might land another orca to keep Moby company—without the help of a lucky harpoon shot. After Newman and his crew observed several pods, they decided it would be a challenge to track whales without aerial support.

When his boat returned to shore, Newman was quizzed about rumors that he’d been trying to capture a new killer whale. Newman admitted he was intrigued by the idea of snagging a second whale— after he found Moby a proper home—but he wasn’t sure how to go about it. “Catching a whale alive is more difficult than people would think. And how would we know if it is a male or female before we shot the harpoon?”

On October 3, the Mother of the Finback Whales died. While Newman and McGeer were whale watching, and Burich was sculpting another model, Maisie Hurley, who’d predicted Moby’s imminent death and a disaster striking Vancouver, suffered a stroke. The extensive Sun coverage of her legacy politely ignored her prognostications about the fate of the whale, and no one suggested that perhaps the disaster she’d predicted was her own. Hurley was gone, and despite her dire warnings, Moby had never looked better—nor had the aquarium. As reports of Moby’s ever-expanding menu filled the papers, the federal government committed $250,000 to an expansion, and the Vancouver Parks Board approved a $750,000 addition to the existing building. Newman had everything he needed—except a proper home for his whale.

On October 9, Moby Doll only took a pair of fish from McLeod at her 2 PM feeding. She had lost her appetite again and didn’t seem to be swimming as smoothly as usual. Word went out to Moby’s medical team that their favorite patient might be sick. As the aquarium’s crew arrived to visit Moby, so did members of her pod.

Other orcas had visited before, but Bauer says that several whales clustered outside the pen, and this time it felt like something different was going on. “They were communicating, but Moby wasn’t like her usual buoyant self.” Then the pod swam away, and Bauer says Moby looked listless, tired, sad.

When Terry McLeod tried feeding Moby again at three, he knelt on the platform to offer her a herring and she took the fish from his hand. But she only took one tiny fish. After a short swim around the pool, Moby came over to McLeod and waited for a back scratch, just like a puppy. McLeod gave her a brisk rub, and then Moby dropped quickly under the surface.

That was when bubbles began rolling up from below the water. This was unusual, but Moby was eating—perhaps it was nothing. It had to be nothing. A minute passed. Then two. Then three. Then hearts sank with their whale.

Bauer knew. “Either it was dead or escaped.” And as Bauer looked at the still water, praying for Moby to surface inside or outside the pen, he knew that she hadn’t escaped.

Moby exhaled through her blowhole for the last time, inhaled the brackish water, her lungs filled, and she suffocated—just as she would have the day she was harpooned if her family hadn’t come to the rescue. After surviving a harpoon, gunfire, and a journey of nearly twenty hours tethered to the end of a rope, Moby Doll drowned.

The men watching Moby’s pen couldn’t believe what they were seeing. They kept hoping that, just maybe, their whale would leap out of the water to demand another treat, another belly scratch.

For months, everyone caring for Moby had braced for the worst, had expected it, but not after she started splashing them and playing with them and eating out of their hands. Not now. Not after they’d all fallen in love with her.

Newman was in a daze. He didn’t want to talk to anyone, especially not the media. McGeer was devastated and angry. “It was like a death in the family.”

McLeod, who’d fed Moby that last fish, felt “broken.”

Bauer felt “shattered.”

Burich stared at the dark water and the raft he’d spent so many days on, trying to convince Moby that she wasn’t alone. He kept hoping she’d surface, or that just maybe she’d discovered a hole in her cage and escaped to freedom.

In 1964, men like Newman, McGeer, Burich, and Bauer didn’t cry—at least not in public—but that didn’t mean their hearts didn’t break. Burich had lived up to his promise. Moby Doll—his victim, his model, his friend—was lying dead at his feet.

Photo by Don McLeod courtesy of Terry McLeod.

And The New York Times obituary.

Here’s the audiobook - currently on sale on Audible & here’s a sample on Spotify